London Calling to the Faraway Towns

I was in the middle of Sunday brunch at the Daily Grill on K Street—a monthly ritual with my friend group—when my Nokia cell phone, the one featured in The Matrix, rang. Loudly. Yes, it actually rang. This was before silent mode or vibration was a thing.

“What are you doing right now?” the voice demanded, skipping pleasantries entirely. This was a work call.

“I’m in the middle of brunch,” I replied, already bracing myself. Sunday work calls weren’t rare in consulting, and when they came, they usually meant dropping everything.

“I can’t say much yet, but the largest merger in the history of financial services is kicking off. We need you on a plane to London. Today. Sync your laptop before you leave—this was when you still had to plug it into a landline to get internet—and look for a briefing package in your email. By the time you land, a work visa should be waiting at customs; they’ll grab it and stamp your passport. Learn everything you can about technology infrastructure and application integration on the flight. Call when you’re in the client offices and can find a telephone.”

This was before mobile phones or credit cards worked reliably across borders, before smartphones and car sharing. International communication depended on landlines. Planning ahead—and having your itinerary written down on paper—wasn’t optional: it was survival.

“How long will the project be?” I asked, already mentally inventorying my wardrobe, planning side trips across Europe.

“Probably a couple of weeks,” he said. “But be prepared for anything.”

Good advice, as it turned out. A couple of weeks became the better part of two years.

Not only did I land a front-row seat in one of the most complex mergers ever attempted, I also found myself living in central London long enough to establish real routines—finding a dry cleaner, memorizing a grocery store layout, knowing which Tube entrance shaved two minutes off the commute. In the world of twenty-something consulting, that counts as putting down roots.

When Less is More

The Right Place at the Right Price

When it became clear that “a couple of weeks” was turning into something longer, my client suggested I trade the central hotel for a flat in a proper neighborhood—somewhere that felt more like living than lodging. Not just any flat—one the bank happened to own. Oil prices had dipped, a wealthy client had fallen behind on payments, and the bank quietly handed me a collateral flat to live in until markets recovered and the account was made whole. It didn’t cost them anything, saved the client money, and gave me room to expand beyond the confines of hotel living and into London’s West End.

Temporary, I was told.

My arrival in London’s West End beat the release of Notting Hill by a few weeks. I missed the filming, but Madonna and Guy Ritchie lived across the square from my flat, which felt like a fair trade.

The flat sat on Prince’s Square, part of a collection of grand residential terraces in Bayswater, only two blocks north of Kensington Palace. From the outside, the architecture was what I think of as British reserved opulence—ornate Victorian façades painted crisp white to catch whatever sunlight managed to break through the fog and mist.

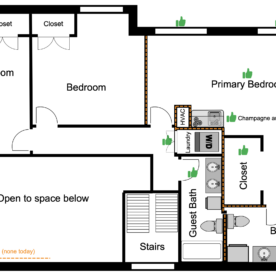

Inside, the flat was shocking. Large by U.K. standards doesn’t begin to cover it: three bedrooms, two full baths, a laundry room, a generous kitchen, and a great room with a spiral staircase opening onto a private rooftop terrace. One side overlooked Prince’s Square; the other stretched toward the Houses of Parliament. Friends who visited were as stunned as I was, remarking that it felt like a filming location for The Real World on MTV.

It wasn’t just size that caught my attention, its style did as well.

In the late ’90s and early 2000s, British minimalism was being reshaped by Cool Britannia—a deliberate move away from the clutter of the ’80s. The open-plan revolution was in full swing. Inspired by converted warehouses in Shoreditch and along the docks, walls came down to create flow between kitchen, dining, and living spaces. Interiors were designed to feel architectural, not decorated.

The flat reflected all of it. Refined. Gallery-like. Minimalist, yet warm without clutter. Natural-tone wood floors and cabinetry paired with a soft, earthy white created architectural warmth. Wall sconces framed furniture and softened the scale of the great room, making it feel inviting even on fog-filled nights.

It was minimalism, but not cold. Spacious, but not empty. A lesson in how restraint, done well, can still feel generous.

My one temptation was to paint the walls warmer—but in the interest of avoiding an oil baron sending a hitman after me like I was starring in one of Guy’s movies, I decided to forgo any permanent changes.

I Bless the Architecture Down in Africa

Years later, while living in Sydney and in the final year of my master’s degree, an all-too-familiar request appeared—this time via email.

Russell, my former boss (by then I’d worked for him twice, at two different companies), had landed a role in his birth country of South Africa. He needed help on a project or two. I had always wanted to live in Africa. He knew my winter break was coming up and invited me to visit.

A direct flight departed Sydney, cut straight over the South Pole, and landed in Johannesburg fourteen hours later.

Almost immediately, I was struck by how modern the city was. It reminded me so much of L.A.’s Westside that I nicknamed it Los Africa. Giant freeways, avenues lined with palm trees. Upscale shopping malls. Modern mid-rise condo buildings. It was… not what I expected.

Later that evening, walking through Melrose Arch—its ultra-modern streetscapes rivaling, and in places surpassing, the best of Beverly Hills’ Rodeo Drive—Russell caught my still-obvious surprise.

“You were expecting kids squatting in the mud, maybe?” he asked.

Images of Africa fed to Americans growing up were often bleak. Infomercials showed famine so frequently they eventually numbed viewers, regardless of empathy. This was also before South Africa had reintroduced itself to the world as the successful and welcoming host of the 2010 FIFA World Cup. “Yes,” I admitted cautiously. “Probably. I didn’t know exactly what I was expecting—but this is far more”—I paused, searching for the right word—“cosmopolitan than what was in my head.”

I knew Johannesburg’s often dark history as a booming gold town. And of course the Aparthied. What I hadn’t fully appreciated was its deliberate evolution towards a modern industrialized and service-based economy—transforming it into the wealthiest city on the continent. Today, the Johannesburg–Pretoria metropolitan area rivals major global cities in economic output, anchored by institutions like the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, one of the world’s largest by market capitalization. If the metro area were a U.S. city it would rank in the top 15, in line with Phoenix and Minneapolis Saint-Paul.

But what struck me most wasn’t South Africa’s large-scale transformation. It was how, at the smallest scale, its architecture worked relentlessly to connect people with the outdoors—rooted in place, climate, and culture, not merely copied from London or New York, as many emerging market cities seem to do.

It felt like a vast new horizon in modernism—one shaped by light, land, and distance—and I was eager to explore it.

Modernist Metros

Surprisingly Spiritual

I decided to add a solo side trip to Madikwe Game Reserve as part of my mini African adventure. An African safari had long been on my bucket list, and Madikwe came highly recommended by Time Out—enough to turn curiosity into momentum. I loaded up a rental car before dawn and set off on the four-hour drive into the African savannah, not entirely sure what to expect.

As the city thinned out, Johannesburg’s freeway system gradually gave way to winding desert roads. At the entrance to the reserve, I left asphalt behind and plunged my VW Polo into the dirt. Clear signage guided me easily to the resort, and I arrived at the main lodge in a cloud of dust and anticipation.

What I didn’t expect was that the first thing to stop me in my tracks wouldn’t be the wildlife.

It would be the architecture.

The resort centered around a main lodge with front desk and concierge services, a restaurant, and a late-night gathering fire pit. Instead of traditional hotel rooms, guests stayed in individual two- to four-bedroom, fully self-contained cabanas.

Despite the cabanas being set close together—for safety from predators who lurk at night; this wasn’t an amusement park—they were positioned with surgical precision to ensure privacy. Which was fortunate, because nearly seventy-five percent of each structure was designed to open fully to the savannah. With views like that, you never wanted anything closed.

The architecture was unapologetically modern: concrete walls, polished cement floors, exposed timber ceilings. Each cabana was complete—private bedroom, kitchen, dining—yet nothing felt sealed off. Accordion doors folded away so entire rooms, even the bathrooms, became part of the landscape. Inside and outside weren’t opposites; they were collaborators.

It was the first time I’d truly experienced the comfort of being indoors while still feeling completely part of nature. The architecture didn’t frame nature as a view; it invited it as a participant.

Dusk and Dawn

Days were structured around game drives at sunrise and sunset, when animals were most active. Mornings began with coffee and hot water bottles to ward off the chill; evenings ended with champagne as the light faded. It was luxury, yes—but quiet and in service of the setting rather than competing with it.

My favorite moment came while using the outdoor shower in my cabana. Mid-rinse, steam rising into the open, dry desert air, a curious elephant wandered to the edge of the patio—maybe fourteen feet away. It paused, assessed me with calm indifference, then moved on as quietly as it arrived. No glass. No barrier. Just shared space and mutual respect. And I’d like to think he left mildly impressed—though without a hint of jealousy.

Safari changed me. In just three days, I felt more connected—to nature, and to myself—than when I arrived. The minimalist luxury of the lodges, paired with the spiritual weight of the landscape, stripped away distraction and sharpened focus on what mattered most: the experience of nature itself. It taught me that modernism doesn’t have to retreat from nature to be refined. Sometimes, the most spiritual spaces are the ones that open themselves completely and trust the landscape to do the rest.

Modernism in the Wild

Just Passing Through (For Three Years)

The mini-adventure technically over, reality briefly intervened. I returned to Sydney to finish my master’s degree, then made a quick stop back in the U.S. to buy a house in Bethesda and establish a mailing address—long enough to convince my dad I was stateside again.

What followed was nearly three years in Africa that expanded my life in ways I hadn’t planned. Professionally, the projects pushed my career further and faster than previous experiences. Personally, it became a place to host family and friends—more safari adventures (including this one with a friend at Kruger National Park), long weekends in Stellenbosch wineries, Cape Town beaches, and dinners that stretched late into the night.

The Melrose Arch Manse

What’s Next – Chapter 11

With a deeper appreciation for letting architecture lead—and for resisting the urge to fill every surface and corner—I returned to the U.S. determined to translate those lessons into my own spaces. London had taught me discipline. Africa had taught me openness. Together, they reshaped how I thought about light, privacy, restraint, and the quiet power of well-considered space.

Today, as Ramiro and I tackle our mid-century restoration in Bethesda, those lessons finally have a place to land. This time, the goal isn’t decoration or accumulation, but allowing the architecture itself to shape the spaces—using structure, proportion, and light to do the heavy lifting.

Chapter 11 is where those ideas stop being abstract and start becoming personal—applied not to borrowed flats or expansive Savannah landscapes, but to our home.